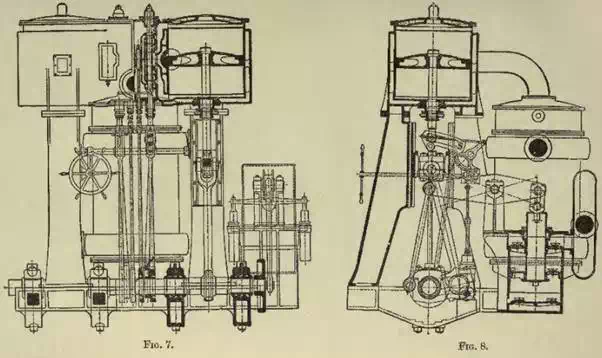

The vertical type of engine, with cylinders at the top and crank-shaft below, was adopted for merchant ships long before it was introduced into the Royal Navy, because it was a necessity in most warships that all the machinery should be kept below the water-line, and horizontal engines alone satisfied this condition. Figs. 7 and 8 show a vertical engine of the type fitted in the mercantile marine.

Vertical engines possess many practical advantages over horizontal engines, especially in connection with the working of the cylinders and pistons, and general accessibility of the engine. When, therefore, the twin-screw system was adopted for armour-clad ships, vertical compound engines were fitted, with a middle line water-tight bulkhead separating the two sets. By dividing the power into two parts, each set of engines, even in a ship of great power, would be of moderate dimensions, and although the whole of the machinery might not in all cases be entirely below the water-line, the parts above would be protected, not only by armour plating, but by a body of coal in addition, the coal-bunkers being continued on each side of the engine room.

This extension of the use of vertical engines has continued and been applied to all classes of vessel, and special means for protecting the cylinders have often been fitted. At the present time new engines for the Navy are being made vertical for all classes of vessel.

Three-cylinder compound engines

As the power of compound engines increased, the dimensions of the low-pressure cylinders became so great that it was found desirable to fit two low-pressure cylinders instead of one, in consequence of the difficulties experienced in obtaining sound castings of large size, and to keep the size of the reciprocating parts as small as possible. This led to what is known as the three-cylinder compound engine, which is simply a modification of the ordinary two-cylinder compound engine. Figs. 9 and 10 show a vertical compound engine of the three-cylinder type.