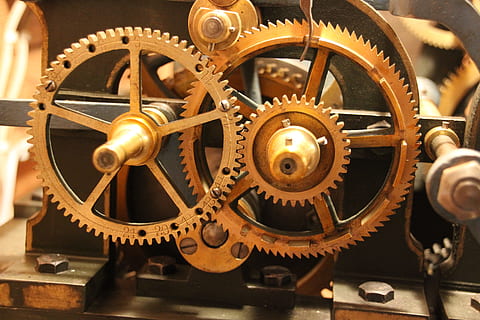

In order to attain the same speed of ship the screw propeller had to be driven at a much greater speed than the paddle-wheel, and as it was not possible in the then condition of mechanical engineering to drive the pistons at a sufficiently high speed to enable the engine shaft to be connected directly to the propeller shafting, the earlier engines used for working screw propellers were geared, so that the screw shaft was caused to revolve at a much higher rate of speed than the engine shaft.

A large spur wheel, keyed on the crank-shaft of the engine, worked into a pinion on the screw propeller shafting, so that the speed of the engine shaft could be multiplied on the screw shaft as might be necessary. Before long, however, such improvements in workmanship and mechanical details were effected, that the speeds both of piston and of revolution could be sufficiently increased to allow direct engines to be fitted.

In these the gearing is left out, and the crank-shaft connected direct to the screw shafting. In many marine engines at the present day, even of the largest size, the mean piston speeds are as high as from 800 to 950 ft. per minute at the maximum power, while in the fast-running engines supplied for torpedo boats and destroyers it rises as high as 1,200 ft. per minute, and in extreme cases to 1,400 ft. It is probable that in the future of marine engineering the speeds may be increased even beyond this, in order to attain increased economy.

Horizontal engines.

The paddle-wheel engines were either vertical or inclined; but when the screw propeller was introduced, and it became possible to place the whole of the propelling apparatus below the water-line, the engine was placed horizontally, and from that time, for about thirty years, the engines of warships were almost always of the horizontal type. One of the great obstacles that had then to be overcome in connecting the crank-shaft of the horizontal engine direct to the screw shafting was the close proximity in which the cylinder was necessarily placed to the centre-line of the ship, owing to the limitation of the beam of the ship, which made it difficult to get a connecting-rod of suitable length to work between the cylinder and the crank.

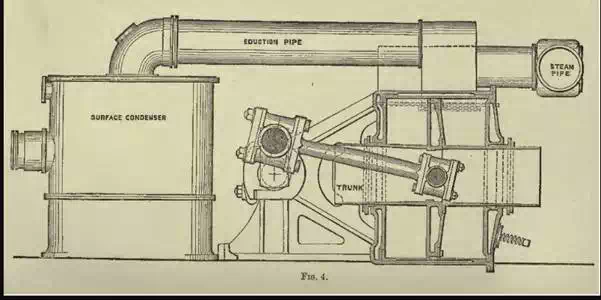

Trunk engines.

Mr. John Penn solved this difficulty by his invention of the trunk engine. In this engine a large hollow trunk, cast on or bolted to the piston, and working through a steam-tight stuffing-box on the end of the cylinder, was substituted for the piston-rod, and the connecting-rod was attached directly to a journal or gudgeon in the centre of the piston itself, as shown in Fig. 4.

Though the use of a large trunk of this description does not at first sight appear desirable, yet the engines of this type have generally worked in a satisfactory manner, and they were amongst the most smooth-working and efficient marine engines employed. With the introduction of high-pressure steam, however, they became obsolete, owing to the difficulty of keeping the trunks in a steam-tight condition.