Many historians discount the effect of the London Treaty, often to their discredit. It and other naval arms control agreements of the Interwar Period from 1918-1939 were exceptional initiatives that restricted the size and power of the world’s navies and helped to cement the alliance that defeated the Axis in World War II. It is no exaggeration to credit the treaty, and related protocols, with dramatically reducing the bloodshed at sea and even with securing ultimate victory for the Allies during the most horrific conflict in recorded human history.

The answer to how the London Treaty changed navies is a major part of its success as an arms control regime. Few international agreements before or since were ever so well regulated, and most important of all, adherence to the treaty crippled the navies of the industrial powers like the US and Great Britain far less than those of the eventual aggressors in the Second World War.

Roots of the London Treaty

After the declaration of armistice on 11 November 1918, the shattered states of Europe began to pick up the pieces and try to determine what went wrong. Questions were asked. People both in and out of government wanted to understand why the Great War began, how it degenerated into a four-year nightmare of slaughter and suffering, and above all else what could be done to prevent another Great War.

For policymakers and the contemporary scholars who informed their decisions in 1918, preventing another war was not a simple exercise in political theory. It was a vital component of establishing a lasting postwar peace. They understood that if they failed, European civilization itself might not survive a renewed conflict. With the advent of chemical weapons, mechanized forces, and long range bombers the danger to the very survival of modern Europe was in jeopardy.

For the victorious Allies, especially the British Empire and America, a major reason they were drawn into the conflict was the growing threat the German High Seas Fleet posed to their interests. Predominantly naval powers at the time, it is very possible that neither would have entered the war had it not been for the perceived threat posed by Germany’s massive naval buildup of the early 1900s. Both judged that preventing another major war hinged on curbing a repeat of this scenario, and stopping any destabilizing arms race in its infancy.

This belief led to one of the first arms control regimes in world history, and likely one of the most sweeping in terms of scope and effect on military deployments. This regime was instituted after the Washington Naval Treaty and fine-tuned by the London Naval Treaties.

London Treaty Particulars

The London Treaty built on the pre-agreed restriction on the ratio of capital ship and cruiser tonnage that could be utilized by the five main signatory powers. This restriction, formally a protocol of the Washington Naval Treaty, had halted a massive buildup of naval vessels in the immediate aftermath of World War I. But although tonnage restrictions had been agreed upon, thus preventing any power from obtaining a significant quantitative advantage over its rivals in any one part of the world, innovation in the design of smaller cruiser class vessels and submarines challenged the success of attempts to limit naval expansions.

Critically, the London Treaty split cruisers into two sub-types: heavy cruisers and light cruisers. The distinction was made based on the maximum size of the vessel’s main guns: 6.1 inches for light and 8 inches for heavy cruisers. Heavies were limited in number and size and lights in total light cruiser tonnage allocated to the entire fleet.

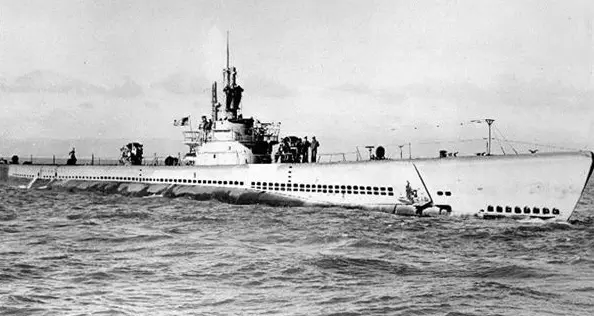

Submarines too were restricted: they could no longer mount large-caliber guns and were expected to obey surface ship conventions when attacking unarmed targets: they had to announce themselves, give their target time to surrender, and make sure the crew was safely removed from the ship- and dumping them on lifeboats didn’t count.

The Value of Naval Arms Control Efforts

Just because the world ended up at war again a scant twenty years after the “War to End All Wars” concluded is a poor reason to denigrate the achievements of London Treaty negotiators. Naval arms control regimes of the 1920’s and 1930s were wildly successful in achieving what they set out to achieve – restricting the size and power of battle fleets in order to prevent an arms race from escalating out of control.

Consider the limitations on the size of guns carried by cruisers. During the 1930s a number of navies were beginning to experiment with putting heavier and heavier guns on cruiser hulls. An excellent example is that of the German pocket battleships like the Graf Spee. Armed with 11″ guns she could out-range any cruiser that challenged her and outrun any battleship that attacked. France and Britain both began designing warships to counter this threat, and which if deployed would have increased the number of heavily armed warships floating around the Atlantic. But the London Treaty forced signatories to make a critical choice: classify these super-cruisers as capital ships and so force a decision between building them or full battleships, or draw down their armament to take advantage of the new tonnage allotments set aside for heavy cruisers.

Because of the London Treaty, fewer powerful warships were built and their capabilities were limited by standing restrictions on the size of cruisers dating back to the Washington agreement. In the case of France, having more ships could have resulted in additional hulls falling into German hands in 1940, which could have changed the outcome of the Battle of the Atlantic.

Submarine restrictions are another fine example. Submarines became less appealing to major navies because they couldn’t be outfitted with cruiser guns and were required to act like surface ships when attacking targets. This meant that the major advantages of submarines – the ability to achieve surprise and deliver lethal strikes before defenders could react – were partly nullified. Having fewer submarines roaming the Atlantic meant that fewer merchant ships were attacked in the opening weeks of World War II. In addition, powers like Japan developed doctrine for submarine use that emphasized their use against warships – very possibly in part to avoid being accused of treaty violations when submarines were deployed.

Changing Navies as a Trust-Building Tool

Possibly the most important aspect of the London Treaty is the effect it had on collaboration and trust between the eventual victorious Allied powers. Although by 1936 a second round of treaty negotiations had lost Japan and Italy as signatories, Britain, France, and the US all joined in to set restrictions on battleship size and armament.

The danger of conflict between two of these three powers was, contrary to common perception, very real during the Interwar Period. The US was isolationist at the time, but very suspicious of British domination of much of the world. France and Britain had remained allied in World War I, but the historic rivalry between the two on land and at sea had not been forgotten. And Britain for her part was cognizant of the growing industrial power of the United States, which had declared its intention to build a navy “second to none.” To some British military thinkers, this was a danger almost as great as that of German rearmament – especially as there had been a real and large movement that supported the US joining the First World War on Germany’s side in the First World War.

Tensions like these may seem petty in retrospect, and certainly were. However, wars have come out of even more ridiculous fears and speculative anxiety. National pride, fear of the shifting balance of power, and old rivalries comprised a significant part of the fabric of the pre-1914 environment.

But the London Treaty went a long way towards mitigating the growth of any hostility between these powerful states. Participation and compliance on the part of each signatory reinforced a sense of trust and fair play which was not found between, say, Japan and the United States. This facilitated cooperation as the international environment degraded in 1938 and 1939 on the eve of the outbreak of war.

Naval Treaty Post-Mortem

The London Treaty couldn’t prevent World War II, but it certainly contributed to the war’s end. Armaments were limited, traditional rivalries curbed, and a foundation of trust was established that helped cement a shaky alliance throughout the darkest days of the 1940s. Indeed, the signatory powers were also several of the founding members of NATO during the Cold War and remain close allies in the 21st Century.

The Treaty restricted the power of naval fleets, and the shortage of hulls was readily rectified by the industrial strength of the United States Navy once it entered the war. It thus did little harm to the Allies’ prospects in the early years of the war, and yet reduced the number and size of guns that were employed by all sides.

The London Treaty changed navies by restricting their power, but it also brought them to better trust one another. It helped forge an alliance that has persisted for the better part of a century.

Comments are closed