European nations have collaborated on a number of military design projects in the past fifty years, among them the Eurofighter, the MEKO series of frigates, and various missiles. Joint aircraft carrier development like that attempted between the UK and France has however never taken off as hoped.

Aircraft Carriers in the 21st Century

Since the Second World War, aircraft carriers have been the cornerstone of the navies of major powers. Their unique ability to provide mobile, sovereign territory to any ocean or international waterway and extend an umbrella of friendly air cover over a region several hundred miles in diameter has made them an indispensible naval asset in almost every major conflict since 1940.

The threat environment for aircraft carriers has become increasingly dangerous as guided missiles and stealthy submarines were adopted by nations that lacked carriers of their own, and the improving lethality of such weapons means that older aircraft carriers active in the 21st century are becoming more and more vulnerable. Every navy with aspirations of regional dominance either has or is trying to acquire modern aircraft carriers and longtime carrier operators like the United States, Britain, and France are all beginning work on their next generation of flattops.

Britain and France in particular have unique histories when it comes to aircraft carrier design and use. Britain led the way in the pre-World War II period when it came to carrier design, and was challenged only by Japan and the United States in this crucial field of naval engineering. But by the end of the war Japan was no longer a naval power and Britain’s empire was rapidly disintegrating. The Royal Navy shed carrier after carrier – often selling them to nations like India or Australia – and by 1979 Britain retired its last big carrier, replacing it with the three baby carriers of the Invincible Class. France, with its military industries ravaged by occupation and war, was late to the game. By the early 1960s, it operated two carriers of indigenous design, and by the early 21st century they were replaced by the Charles de Gaulle, the only nuclear powered carrier not operated by the United States.

British-French Carrier Replacement Requirements

The de Gaulle had a troubled development history and took many more years than anticipated to resolve major construction defects. Before she even became reliably operational, France had sold its only other carrier to Brazil and could only keep a carrier at sea for part of any given year. Two of Britain’s baby carriers were retired between the end of the Cold War and 2011, leaving only the aging HMS Illustrious to lead the fleet. So as the second decade of the 21st Century began, it was clear to both France and Britain that new British aircraft carriers and new French aircraft carriers would be needed around the same time.

This realization led to a cooperative effort on the part of the two nations to develop the first British-French carrier in history, and in fact the first aircraft carrier to be designed by two nations working together to achieve mutually supportive goals. European nations had cooperated on a number of military projects during the Cold War; the Jaguar fighter, the Tornado attack aircraft, the Alpha Jet, the Eurofighter Typhoon, and the Eurocopter are flying examples of pan-European cooperation. A number of missile projects were undertaken jointly by European powers including the Milan and HOT anti-tank missiles, and the Roland surface to air missile. Even the MEKO family of warships, though built by Germany, was designed for NATO and allied nations with the input of the buyer nations.

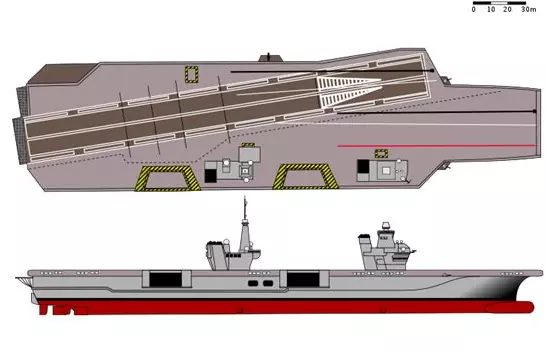

But an aircraft carrier is a different animal altogether compared to a missile or jet- the joint design proposed by Britain was to displace over seventy thousand tons and operate several dozen combat aircraft. Such collaboration would require significant efforts by both sides to suppress long standing national preferences in naval design, yet produce a class of new British and new French aircraft carriers that would be capable of withstanding 21st century threats.

The Power Plant Issue

Sticking points in the design process emerged quite soon after formal cooperation began. A major, immediate problem that had to be resolved was the form of propulsion to be used by the new British-French carrier design.

Britain has never taken to utilizing nuclear power plants in any of its vessels save for submarines. Nuclear power plants are highly efficient and do allow a vessel to operate without refueling for years at a time. But there is a high cost associated with nuclear reactors, both in terms of initial investment and certain design redundancies that must be in place to protect the power plant from a meltdown due to accident or damage. Nuclear reactors, as evidenced by Chernobyl and Fukushima (not to mention known and possibly unknown events in the United States) are always at risk of failing if they cannot be cooled. Ambient radioactivity must also be monitored and adequate shielding installed to prevent long term exposure from affecting the crew. And reactors require specially trained personnel to ensure they are maintained and operated safely.

But France used and continues to use nuclear power in its submarine force as well as the Charles de Gaulle, and it had become a point of pride for France that it maintained the only nuclear carrier that wasn’t American made. Much as France maintains its own nuclear deterrent as a point of national pride, it came to view using nuclear power in its carriers to be a statement, and that moving to conventional power would be a technological step backwards for the French Navy.

Though not a deal breaker, the argument over propulsion decreased French interest in the program, and contributed to its ultimate failure.

The Collaboration Disintegrates: Sarkozy Pulls France Out

The full reasons for the failure of the British-French carrier project will likely never be known, but certain aspects of the failure seem clear.

Timelines are difficult to coordinate between two major bureaucratic organizations within a single country, and trying to sync the needs of two different countries is nigh impossible. After the retirement of Foch and its sale to Brazil, only the de Gaulle is left provide carrier air cover for French fleets.

But lingering flaws require it to spend the better part of two years out of every six years in drydock for repairs – and this is in addition to the normal maintenance downtime needed by big naval vessels. A new French aircraft carrier was authorized in the 2008 defense budget and was likely hoped that a new carrier could enter service by the next time the de Gaulle went in for its long maintenance. But Britain, though originally hoping to bring its first new carrier online in 2014, pushed back that date to 2020. If accompanied by delays in the design itself, this may well have dimmed French hopes for a push to return to its two-carrier fleet standard.

Finances are also likely a key player. The 2008 financial collapse and the ongoing turmoil in Europe due to a probable Greek default on its debt has made any major military expenditure a risky proposal. French President Sarkozy, upon pulling out of the British-French aircraft carrier project in 2008, cited the desire to use nuclear power as a key point against continued collaboration. But a simpler explanation is that in an era of budget cuts, France is having to rethink its carrier fleet and consider maintaining only one for years to come.

If budgets remain tight, and Britain holds to its plan to keep the HMS Queen Elizabeth as its only active carrier with her sister, HMS Prince of Wales left in reserve, it is not inconveivable that France could decide to maintain one carrier and trade off deployment duties with its NATO partner, Britain.

Comments are closed