Analog computer, any of a class of devices in which continuously variable physical quantities such as electrical potential, fluid pressure, or mechanical motion are represented in a way analogous to the corresponding quantities in the problem to be solved. The analog system is set up according to initial conditions and then allowed to change freely. Answers to the problem are obtained by measuring the variables in the analog model. See also digital computer.

The earliest analog computers were special-purpose machines, as for example the tide predictor developed in 1873 by William Thomson (later known as Lord Kelvin). Along the same lines, A.A. Michelson and S.W. Stratton built in 1898 a harmonic analyzer (q.v.) having 80 components. Each of these was capable of generating a sinusoidal motion, which could be multiplied by constant factors by adjustment of a fulcrum on levers. The components were added by means of springs to produce a resultant. Another milestone in the development of the modern analog computer was the invention of the so-called differential analyzer in the early 1930s by Vannevar Bush, an American electrical engineer, and his colleagues. This machine, which used mechanical integrators (gears of variable speed) to solve differential equations, was the first practical and reliable device of its kind.

Most present-day electronic analog computers operate by manipulating potential differences (voltages). Their basic component is an operational amplifier, a device whose output current is proportional to its input potential difference. By causing this output current to flow through appropriate components, further potential differences are obtained, and a wide variety of mathematical operations, including inversion, summation, differentiation, and integration, can be carried out on them. A typical electronic analog computer consists of numerous types of amplifiers, which can be connected so as to build up a mathematical expression, sometimes of great complexity and with a multitude of variables.

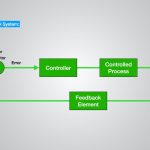

Analog computers are especially well suited to simulating dynamic systems; such simulations may be conducted in real time or at greatly accelerated rates, thereby allowing experimentation by repeated runs with altered variables. They have been widely used in simulations of aircraft, nuclear-power plants, and industrial chemical processes. Other major uses include analysis of hydraulic networks (e.g., flow of liquids through a sewer system) and electronics networks (e.g., performance of long-distance circuits).