Industrial ships are those whose function is to carry out an industrial process at sea. A fishing-fleet mother ship that processes fish into fillets, canned fish, or fish meal is an example. Some floating oil drilling or production rigs are built in ship form. In addition, some hazardous industrial wastes are incinerated far at sea on ships fitted with the necessary incinerators and supporting equipment. In many cases, industrial ships can be recognized by the structures necessary for their function. For example, incinerator ships are readily identified by their incinerators and discharge stacks.

Passenger carriers

Most passenger ships fall into two subclasses, cruise ships and ferries.

Cruise ships

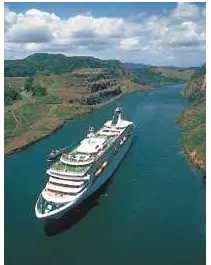

Cruise ships are descended from the transatlantic ocean liners, which, since the mid-20th century, have found their services preempted by jet aircraft. Indeed, even into the 1990s some cruise ships were liners built in the 1950s and ’60s that had been adapted to tropical cruising through largely superficial alterations—e.g., the addition of swimming pools and other amenities to suit warm-latitude cruising areas. However, most cruise ships now in service were built after 1970 specifically for the cruise trade. Since most of them are designed for large numbers of passengers (perhaps several thousand), they are characterized by high superstructures of many decks, and, since their principal routes lie in warm seas, they are typically painted white all over. These two characteristics give them a “wedding cake” appearance that is easily recognizable from great distances. Closer examination usually reveals a large number of motor launches carried aboard for the ferrying ashore of passengers. Many cruise ships have stern ramps, much like those found on cargo-carrying roll-on/roll-off ships, in order to facilitate the transfer of passengers to the launches and to serve as docking facilities for small sporting boats.

The above features present the principal challenge to the cruise-ship designer: providing the maximum in safety, comfort, and entertainment for the passengers. Thus, isolation of machinery noise and vibration is of high importance. Minimizing the rolling and pitching motions of the hull is even more important—no extreme of luxury can offset a simple case of seasickness. Since cruising is a low-speed activity, propulsive power is usually much lower than that found in the old ocean liners. On the other hand, electrical power is usually of much greater magnitude, mainly because of demands by air-conditioning plants in tropical waters. The typical large cruise ship built since 1990 is powered by a “central station” electric plant—i.e., an array of four or more identical medium-speed diesel engines driving 60-hertz alternating-current electrical generators. This electrical plant supplies all shipboard power needs, including propulsion. Since all power flows from a single source, propulsion power can be readily diverted to meet increased air-conditioning loads while the ship is in port.