The world’s cargo ships are getting big, really big. No surprise, perhaps, given the volume of goods produced in Asia and consumed in Europe and the US. But are these giant symbols of the world’s trade imbalance growing beyond all reason?

What is blue, a quarter of a mile long, and taller than London’s Olympic stadium?

The answer – this year’s new class of container ship, the Triple E. When it goes into service this June, it will be the largest vessel ploughing the sea.

Each will contain as much steel as eight Eiffel Towers and have a capacity equivalent to 18,000 20-foot containers (TEU).

If those containers were placed in Times Square in New York, they would rise above billboards, streetlights and some buildings.

Or, to put it another way, they would fill more than 30 trains, each a mile long and stacked two containers high. Inside those containers, you could fit 36,000 cars or 863 million tins of baked beans.

This image from Maersk shows what 18,000 shipping containers look like in the wrong place

The Triple E will not be the largest ship ever built. That accolade goes to an “ultra-large crude carrier” (ULCC) built in the 1970s, but all supertankers more than 400m (440 yards) long were scrapped years ago, some after less than a decade of service. Only a couple of shorter ULCCs are still in use. But giant container ships are still being built in large numbers – and they are still growing.

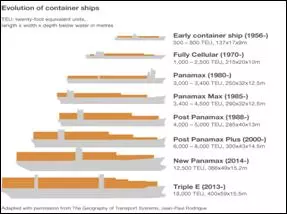

It’s 25 years since the biggest became too wide for the Panama Canal. These first “post-Panamax” ships, carrying 4,300 TEU, had roughly quarter of the capacity of the current record holder – the 16,020 TEU Marco Polo, launched in November by CMA CGM.

In the shipping industry there is already talk of a class of ship that would run aground in the Suez canal, but would just pass through another bottleneck of international trade – the Strait of Malacca, between Malaysia and Indonesia. The “Malaccamax” would carry 30,000 containers.

The current crop of ultra-large container vessels can navigate the Suez – just – but they are only able to dock at a handful of the world’s ports. No American harbour is equipped to handle them.

The sole purpose of the soon-to-be-launched Triple E ships will be to run what’s called a pendulum service for Maersk – the largest shipping company in the world – between Asia and Europe.

They arrive in Europe full, and when they leave a significant proportion of containers carry nothing but air. (At any given moment about 20% of all containers on the world’s seas are empty.)

“Ships have been getting bigger for many years,” says Paul Davey from Hutchison Ports, which operates Felixstowe in the UK, one of the likely ports of call of the Triple E.

“The challenge for ports is to invest ahead of the shipping capacity coming on-stream, and to try and be one step ahead of the game.”

“When you get bigger ships, you can more efficiently carry more cargo, so the fuel footprint you get per tonne of cargo is smaller”

Overcapacity in the world’s ports means there is huge competition for business. Operators cannot afford to get left behind, says Marc Levinson, author of The Box – How the Shipping Container Made the World Smaller and the World Economy Bigger.

“The ports are placed in a difficult competitive position here because the carriers are basically saying to them, ‘If you don’t expand – if you don’t build new wharves and deepen the harbours and get high speed cranes, we’ll take our business someplace else.'”

These big beasts of the sea present ports with other challenges too.

Ship owners also want vessels to be unloaded and loaded within 24 hours, which has various knock-on effects. More space is needed to store the containers in the harbour, and onward connections by road, rail and ship need to be strengthened to cope with the huge surge in traffic.

Felixstowe, which handles 42% of the UK’s container trade, has 58 train movements a day, but plans to double that after it opens a third rail terminal later this year.

Bigger vessels also behave differently in the water. The wash created by a large ship can be enough to cause other ships moored in a harbour to break free – just as the passenger liner SS City of New York did in 1912 when the Titanic set out on her maiden voyage.

“These days with the increase in traffic, we experience this more and more often,” says Marco Pluijm, a port engineer working for Bechtel. “A simple thing you can do is just slow ships down and add some tug boats for better manoeuvring – but that all has cost implications.”

There are currently 163 ships on the world’s seas with a capacity over 10,000 TEU – but 120 more are on order, including Maersk’s fleet of 20 Triple Es.

Bearing in mind that the carbon footprint of international shipping is roughly equivalent to that of aviation – some 2.7% of the world’s man-made CO2 emissions in the year 2000, according to the International Maritime Organization – the prospect of these leviathans carving up the oceans in ever greater numbers is likely to be a source of concern for green consumers.

Maersk, however, argues that the Triple E is the most environmentally friendly container ship yet. (The three Es in the name stand for economy of scale, energy efficiency and environmentally improved.)

| Big beasts | ||

| Name | Size | Record |

| Marco Polo (CMA CGM) | ||

| 396mx54m | Largest container ship now afloat at 16,020 TEU – 1,980 TEU less than the Triple E. Launched November 2012. |

| E class (Maersk) | ||

| 397mx56m | Longest ship now on the sea – 3m shorter than Triple E. The first of eight, Emma Maersk, was launched in 2006. |

| T1 class supertanker (Euronav) | ||

| 380mx68m | Biggest tanker, holding 503m litres of oil. Also strongest ship, carrying up to 442,000t. Launched 2003. Two remain in service. |

| Oasis of the Seas (Royal Caribbean) | ||

| 362mx65m | Biggest passenger ship, carrying 8,072 people. Launched 2009. Sister ship of Allure of the Seas. |

Although it will only be three metres longer and three metres wider than the 15,500-TEU Emma Maersk, its squarer profile allows it to carry 16% more cargo.

Re-designed engines, an improved waste-heat recovery system, and a speed cap at 23 knots – down from 25 – will produce 50% less carbon dioxide per container shipped than average on the Asia-Europe route, Maersk calculates.

The Triple E’s bridge has been brought forward so containers can be stacked higher with no loss of visibility

“When you get bigger ships, you can more efficiently carry more cargo, so the carbon footprint you get per tonne of cargo is smaller,” says Unni Einemo from the online trade publication Sustainable Shipping. “So on that basis, big is beautiful.”

To achieve maximum fuel efficiency, however, a ship has to be fully loaded.

“They are massive ships, and a really big ship running half-full is probably less energy-efficient overall than a smaller ship running with a full set of containers,” says Einemo.

Widening the Panama canal

There was 6in to spare when the USS Missouri passed through the Panama Canal in 1945. Wider locks are due to be completed in 2014, allowing 49-metre-wide “New Panamax” ships to use it. But it will remain off limits to the largest container ships.

Maersk’s Triple Es will be going into service at a time when growth in the volume of goods to be shipped is comparatively low – some experts don’t expect it to pick up until 2015. But the world’s container fleet capacity is expected to grow by 9.5% this year alone, as Maersk and others receive the ships they ordered years ago.

Some of the extra capacity will be absorbed in the new practice of slow steaming – industry-speak for sailing more slowly. Sailing at 12-15 knots instead of 20-24 knots brings enormous savings on fuel – but it does mean that extra ships are required to transport the same volume of goods in the same timescale.

Maersk are counting on container trade continuing to grow at 5-6% – less than half the growth rate of seven years ago, but enough to recoup the company’s investment in the Triple Es, which cost $190m (£123m) each.

“The history of container shipping involves ship lines taking huge gambles,” says Marc Levinson, who points to a trend for some American and European companies to move manufacturing back from Asia.

“There are a lot of people in the shipping industry who aren’t sure that Maersk is on the right track,” he says.

Jean-Paul Rodrigue at Hofstra University believes that big container ships like the Triple E will prove their value on specific trade routes, nonetheless.

“Each time a new generation comes along, there’s the argument ‘Oh is this going a little too far this time – is there enough port trade to justify this?'” he says.

“But each time the ship class was able to put itself in the system and provide a pretty good service.”